|

Failed Grafts

Although excellent rates of 1-year patient and graft survival have

been achieved in recent years for all

types of technically successful pancreas transplants (SPK, PTA, PAK) a significant number of grafts are still lost in the early post-implantation period, due to a variety

of surgical complications. Graft losses

due to leaks, bleeding, thrombosis, infections and early pancreatitis are grouped together under the

category of technical failure. Currently the number of surgical complications

is disproportionately high in comparison to the number of graft loses due to

acute rejection. Thrombosis continues to be the leading cause of

non-immunological graft loss (5.8-16.4 %) with higher rates seen in PAK and PTA

cases with enteric drainage. The pancreas has intrinsically a low blood flow compared to other solid

organs. Perioperative inflammation and edema, as well as microvascular and

endothelial damage relating to donor factors and organ preservation, all

contribute to further compromise blood flow in the early post-transplant period

leading to thrombosis. Correspondingly

longer cold ischemia times have been associated with increased incidence of

graft thrombosis. Acute rejection is suspected to play a role in some patients with early

graft thrombosis. HLA mismatches appear

not to impact on the incidence of graft

loss due to technical failures, however, HLA mismatch does have an overall negative impact on graft survival. Graft pancreatectomies:

Guidelines for gross and histological evaluation Graft pancreatectomies usually consist of the whole pancreas and attached portion of duodenum. The latter is present in continuity either

with a loop of recipient's small intestine

or a patch of urinary bladder wall. Systematic histological evaluation of failed grafts is necessary for accurate

classification of the cause of graft

loss. Minimun histological sampling

should include cross sections of all large vessels and several sections from

the parenchyma to include an adequate number of medium sized and small vessels.

The number of histological

sections depends on each case; the most

important structures should be sampled routinely. Gross evaluation: - Large arteries and veins: evaluate for thrombosis (recent and

organized), endotheliitis, arteriris, transplant vasculopathy) - Random samples from parenchyma (viable and necrotic, usually 3-5

sections): evaluate for evidence of ischemia/pancreatitis, acute rejection, chronic rejection, presence

of infectious organisms, etc.). - Area of anastomosis: evaluate for dehiscences (leaks) - Samples from any other lesions: masses (i.e. PTLD), cysts, abscesses,

lymph nodes, etc.) Ancillary studies: - Immunoperoxidase

stains for insulin and glucagon should be perfomed to evaluate for selective

destruction of beta cells (recurrence of autoimmune destruction). These cases show near normal parenchyna with

no significant evidence of fibrosis/acinar loss (chronic rejection). - Frozen tissue for

immunfluorescence stains for immunoglobulins and complement in cases suspected to represent

hyperacute rejection. - Electron

microscopy: May be helpful in recurrence of diabetes type 1. Histological

evaluation: Based on the histological findings pancreatectomies can be broadly

classified as follows. 1)

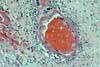

PURE VASCULAR THROMBOSIS IN AN OTHERWISE NORMAL PANCREAS In these grafts the only pathological changes

consist of recent vascular thrombosis and bland ischemic parenchymal

necrosis. There is no underlying vascular pathology or any other specific

histological change. (In early

graft loss the most important histological determination relates to blood

vessels.) The majority of these grafts (78%) are lost in

less than 48 hours after transplantation and we have never seen this pattern in

grafts lost after the first 2 weeks post-transplantation. In the case of early thrombosis, the lack of obvious histological changes associated with

the thrombosis does not rule out ultrastructural

or subtle functional damage in these organs, since older donor age and longer

cold ischemia times are associated with increased risk for early

thrombosis. 2) HYPERACUTE

ALLOGRAFT REJECTION Hyperacute rejection in the pancreas is indistinguishable from hyperacute rejection affecting other organs, and it is characterized

by necrosis of arteries and veins with

secondary massive and immediate

thrombosis and parenchymal necrosis. We

have rarely seen rapid graft loss (within 1-12 hours post-transplantation) with

extensive fibrinoid necrosis of arteries and veins with associated massive

vascular thrombosis and parenchymal necrosis. Immunohistochemical studies in these cases were positive for IgG and C3 in the wall of blood vessels.

3)

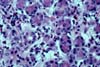

ACUTE ALLOGRAFT REJECTION Graft loss secondary to acute allograft rejection

(other than hyperacute rejection) can be seen from the first week to few months

post-transplantation (in our experience

at a mean of 5.1 weeks). These cases show endotheliitis and various degrees of necrotizing arteritis (acute

rejection Grades IV-V). Graft losses

in the first months may result from a combination of infection and rejection. 4)ACUTE AND CHRONIC REJECTION Patients with with persistent (biopsy proven) acute allograft rejection can show early interstitial fibrosis

and acinar loss consistent with chronic rejection, starting in the second month

post-transplantation. In our experience graft pancreatectomies with combined

features of acute and chronic rejection

were resected at times ranging from 6 weeks to 20 months (mean 6.6 months). 5) PANCREATITIS AND

PERIPANCREATITIS Necrotizing infectious duodeno-pancreatitis with or without abscess

formation can present at variable times post-transplantation but occur often

early on (mean 3.6 months); a vaiety of

organisms can be cultured from these grafts, most commontly enterobacteria

(Enterobacter cloacae, Proteus mirabilis) and Methicillin resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)). Fungal infections (Often Candida) and mixed

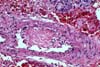

infection are not uncommon. 6) CHRONIC REJECTION These pancreatectomies show extensive interstitial fibrosis/ acinar

atrophy and transplant (obliterative) arteriopathy. This pattern can be seen after few months post-transplantation

but is more commonly seen after the second year post-transplantation (mean 28.6

months , range 4 to 81 months). Many of

these grafts do not show any significant concurrent acute rejection. Chronic rejection is the most important cause of graft loss after the

first 6 months post-transplantation. 7) POST-TRANSPLANT

LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER In our center allograft pancreatectomies for PTLD were performed in 4

patients in the second month post-transplantation and in one patient in month

12 (mean 5 months). The histological findings are described in the EBV section.

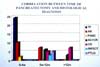

INCIDENCE OF

VASCULAR THROMBOSIS Recent thrombosis is seen to some degree in all cases of early graft

loss due to acute allograft rejection with vascular involvement (superimposed

on endotheliitis or arteritis) . All cases with chronic

rejection show scattered vessels with thrombosis (acute and chronic; this

typically involves medium size to small

arteries and veins. Acute vascular thrombosis in one or more large vessels can lead to

graft pancreatectomy in otherwise well

functioning allografts. In these cases the thrombosis always occurs in

abnormal blood vessels, either showing transplant arteriopathy or lesions

consistent with healing vasculitis/endotheliitis. The presence of transplant

arteriopathy (one of the histological features of chronic rejection) is

strongly associated with recent and

organized thrombosis. Correspondingly old (organized) thrombosis is seen almost

invariably in pancreatectomies with chronic rejection. As expected, progressive graft fibrosis (correlating with increasing grades of

chronic rejection) and the presence of transplant arteriopathy are directly related to the time elapsed after transplantation. Thrombosis is insignificant in the pancreatectomies performed for infectious

processes. REFERENCES Gruessner RWG, Dunn

DL, Gruessner AC, Matas AJ, Najarian JS, Sutherland DER: Recipient risk factors

have an impact on technical failure and patient and graft survival rates in

bladder-drained pancreas transplants. Transplantation

1994;57:1598-1606. Gruessner RWG,

Sutherland DER, Troppman C et al: The surgical risk of pancreas transplantation

in the Cyclosporine era: An overview. J

Am Coll Surg 1997;185:128-44. Gruessner AC and

Sutherland DER: Analysis of United States (US) and Non-US pancreas transplants

as reported to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) and to the

United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). In: Clinical Transplants 1998, pp

53-71, Cecka and Terasaki, Eds. UCLA Tissue Typing Laboratory, Los Angeles

California. Gruessner RWG,

Troppmann C, Barrou B et al: Assessment of donor and recipient risk factors on

pancreas transplant outcome. Transplant Proc 1994;26:437-8. Feitosa Tajra LC,

Dawhara M, Benchaib M, Lefrancois N, Martin X, Dubernard JM: Effect of the

surgical technique on long-term outcome of pancreas transplantation. Transpl

Int 1998;11:295-300. Morel P, Gillingham

KJ, Moudry-Munns KC, Dunn DL, Najarian

JS, Sutherland DER: Factors influencing pancreas transplant outcome: Cox

proportional hazard regression analysis of a single institution's experience

with 357 cases. Transplant Proc 1991;23:1630-33. Osaki CF, Stratta R,

Taylor RJ, Langnas AN, Bynon JS, Shaw BW: Surgical complications in solitary

pancreas and combined pancreas-kidney transplantations. Am J Surg 1992;164:546-51. Sollinger HW:

Pancreatic transplantation and vascular graft thrombosis. J Am Coll Surg

1996;182:362-3. Stratta RJ: Graft

failure after solitary pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proc 1998;30:289. Stratta RJ: Patterns

of graft loss following simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proc 1998;30:288. Stratta RJ, Gaber

AO, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Reddy KS, Egidi MF, Grewal HP: Allograft pancreatectomy

after pancreas transplantation with systemic-bladder versus portal-enteric

drainage. Clin Transplant 1999;13:465-72. Kuo PC, Wong J,

Schweitzer EJ, Johnson LB, Lim JW, Bartlett ST: Outcome after splenic vein

thrombosis in the pancreas allograft. Transplantation 1997;64:933-5. Benedetti E,

Troppmann C, Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE, Dunn DL, Gruessner WG: Pancreas graft

loss caused by intra-abdominal infection. A risk factor for a subsequent

pancreas retransplantation. Arch Surg 1996;131:1054-60. Bragg LE, Thompson

JS, Burnett DA, Hodgson PE, Rikkers LF: Increased incidence of pancreas-related

complications in patients with postoperative pancreatitis. Am J Surg

1985;150:694-7. Büsing M, Hopt UT,

Quacken M, Becker HD, Morgenroth K: Morphological studies of graft pancreatitis following

pancreas transplantation. Br J Surg 1993;80:1170-3. Sugitani A, Gritsch

HA, Shapiro R, Bonham CA, Egidi MF, Corry RJ: Surgical complications in 123

consecutive pancreas transplant recipients: Comparison of bladder and enteric

drainage. Transplant Proc 1998;30:293-4. Troppmann C,

Gruessner AC, Benedetti E et al:Vascular graft thrombosis after pancreatic

transplantation: univariate and multivariate operative and nonoperative risk

factor analysis. J Am Coll Surg 1996;182:285-316. Wright FH, Wright C,

Ames SA, Smith JL, Corry RJ: Pancreatic allograft thrombosis: Donor and

retrieval factors and early postperfusion graft function. Transplant Proc

1990;22:439-41. Reddy KS, Stratta

RJ, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Alloway R, Egidi MF, Gaber AO: Surgical complications

after pancreas transplantation with portal-enteric drainage. J Am Col Surg

1999;189:305-13. Grewal HP, Garland

L, Novak K, Gaber L, Tolley EA, Gaber AO: Risk factors for postimplantation

pancreatitis and pancreatic thrombosis in pancreas transplant recipients.

Transplantation 1993;56:609-12. Tollemar J, Tydén G,

Brattström C, Groth CG: Anticoagulation

therapy for prevention of pancreatic graft thrombosis: Benefits and risks.

Transplant Proc 1988;3:479-80. Sasaki T, Pirsch JD,

Ploeg RJ et al: Effects of DR mismatch

on long-term graft survival in simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation.

Transplant Proc 1993;25:237-8. Drachenberg CB,

Papadimitriou JC, Klassen DK et al.: Evaluation of pancreas transplant needle biopsy: reproducibility and

revision of histologic grading system. Transplantation 1997;63:1579-86. Drachenberg CB,

Papadimitriou JC, Klassen DK et al: Chronic pancreas allograft rejection:

morphologic evidence of progression in needle biopsies and proposal of a

grading scheme. Transplant Proc 1999;31:614. Drachenberg CB,

Abruzzo LV, Klassen DK et al: Epstein-Barr virus-related post-transplantation

lymphoproliferative disorder in pancreas allografts: histological differential

diagnosis from acute allograft rejection. Hum Pathol 1998;29:569-77. Grekas D, Alivanis

P, Derveniotis F, Papoulidou N, Kaklamanis N, Tourkantonis A: Influence of

donor data on graft function after cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplant

Proc 1996;28:2957-8. Douzdjian V,

Gugliuzza KG, Fish JC: Multivariate analysis of donor risk factors for pancreas

allograft failure after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Surgery

1995;118:73-81. Odorico JS, Heisey

DM, Voss BJ et al.:Donor factors affecting outcome after pancreas

transplantation. Transplant Proc 1998;30:276-7. Tso PL, Elkhammas

EA, Henry ML et al.: Risk factors of long-term survivals in combined

kidney/pancreas transplantation: A multivariate analysis of 259 recipients.

Transplant Proc 1995;6:3104. Hawthorne WJ,

Griffin AD, Lau H et al.: Experimental hyperacute rejection in pancreas

allotransplants. Transplantation 1996;62:324-9. Hesse UJ and

Sutherland DE: Influence of serum amylase and plasma glucose levels in pancreas

cadaver donors on graft functioning recipients. Diabetes 1989;38:1-3.

Please mail comments, corrections or suggestions to the TPIS administration at the UPMC.

If you have questions, please email TPIS Administration. |

|