"Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis"(1) is term that has been coined to define a unique or unusual clinical and histopathological presentation of type B viral hepatitis in liver allograft recipients(2). However, it is also seen with other viruses, such as HCV(3, 4) and in other severely immunosuppressed patients, such as renal and bone marrow allograft recipients and those with AIDS(3, 5-10). Other names have also been used to describe this entity. These include "fibrosing cytolytic hepatitis"(11), which draws attention to the degenerative changes in the hepatocytes, including cell swelling and cytolysis. "Steatoviral" and "fibroviral" hepatitis have been used to draw attention to the heavy viral burden that causes swelling of the endoplasmic reticulum and hepatocellular degenerative changes, including steatosis and to the fibrosis that develops despite a paucity of inflammation(12).

Pathophysiology

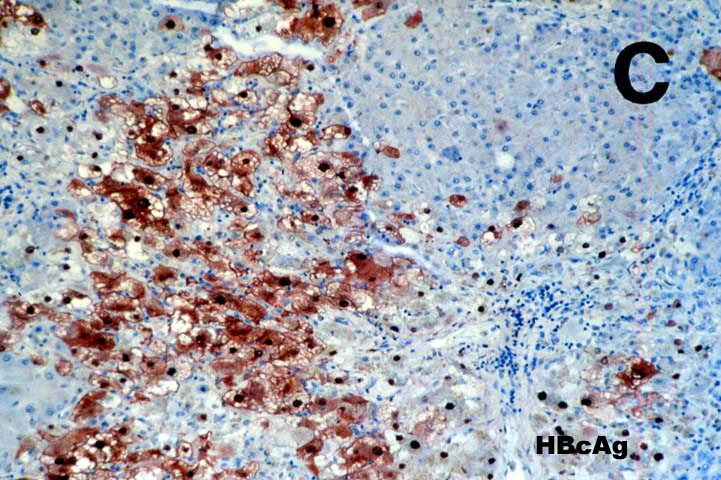

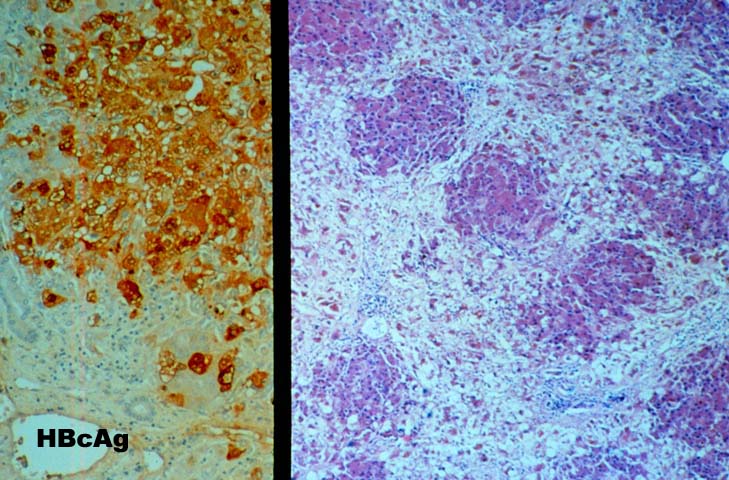

When FCH was first described, it was postulated that the B virus was capable of directly injuring the hepatocytes, because of under these special circumstances viral proliferation was unchecked, resulting in massive overproduction of viral particles and antigens(2). Subsequent studies did indeed show high levels of viral replication and antigen expression, re-enforcing the notion that the B virus can be cytopathic under certain circumstances(1, 2, 11-16). Further studies of HBV+ liver allograft recipients have shown that this more aggressive clinical and histopathological presentation may be related to infection with pre-core mutants of the B virus(5-7, 17-20).

Since FCH is unusual in the general population, the common factor of immunodeficiency in the diverse patient populations mentioned above, is likely to be the most important predisposing factor. This leads to unchecked viral replication. The effect, if any, of MHC non-identity between the liver and the immune system is unknown. However, the occurrence of FCH outside of liver transplantation, where there is MHC identity between the immune system and the liver, suggests that non-identity is not a crucial factor(1, 2, 11-14, 21).

Clinical Presentation

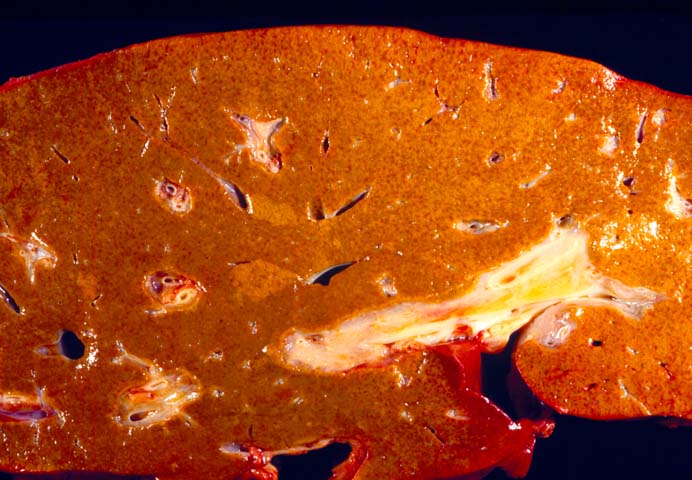

In contrast to elevations of the liver injury tests as is seen in the initial presentation of most cases of hepatitis B and C after transplantation, FCH is usually accompanied by dramatic clinical symptoms. These include nausea, malaise, jaundice, abdominal pain, and progression to hepatic failure and encephalopathy over a periods of weeks to a few months. Biochemical evidence of liver dysfunction and injury are usually skewed toward a cholestatic profile, as might be expected from the name, with marked elevation of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase. Unfortunately, many patients rapidly progress to liver failure. Thus a histopathological diagnosis of "FCH" carries ominous clinical connotations, although prolonged survival in a patient treated with ganciclovir has been reported(22). Treatment of such patients with anti-viral agents, might initially decrease viral replication, but because of the concomitant lack of viral cytotoxicity, viral mutants can arise.

Histopathological Findings

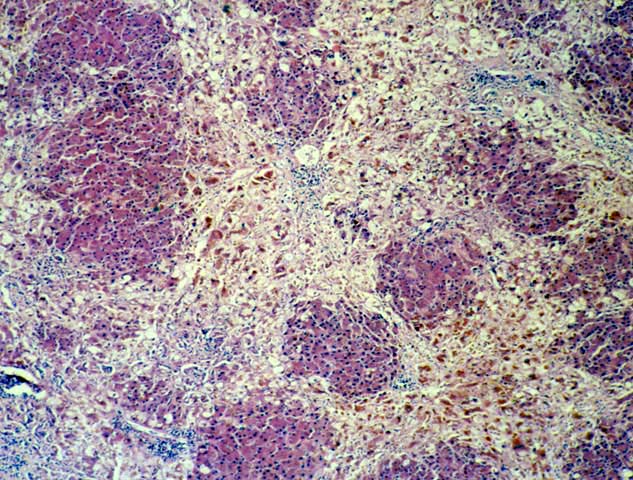

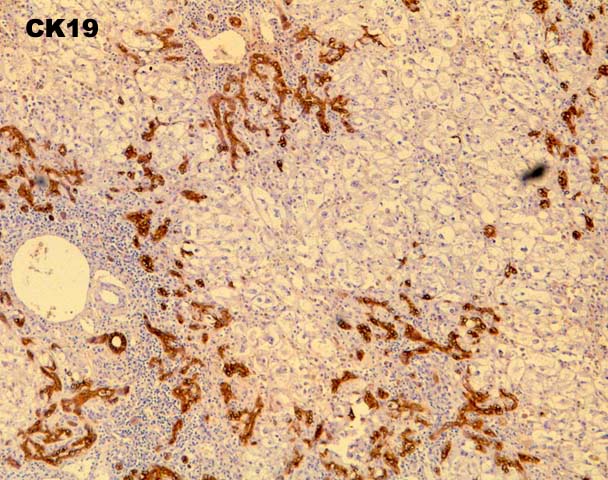

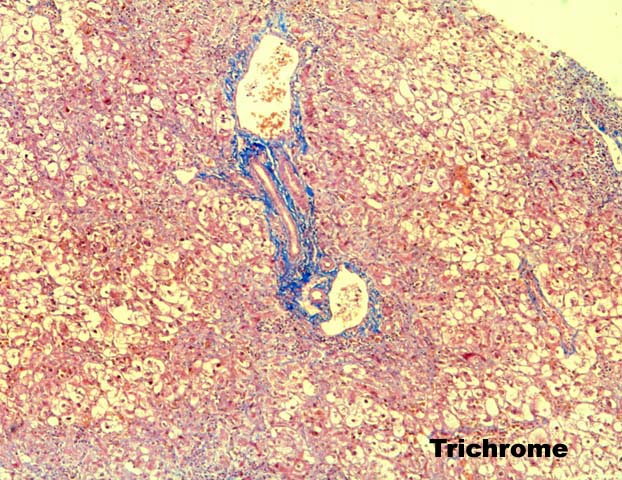

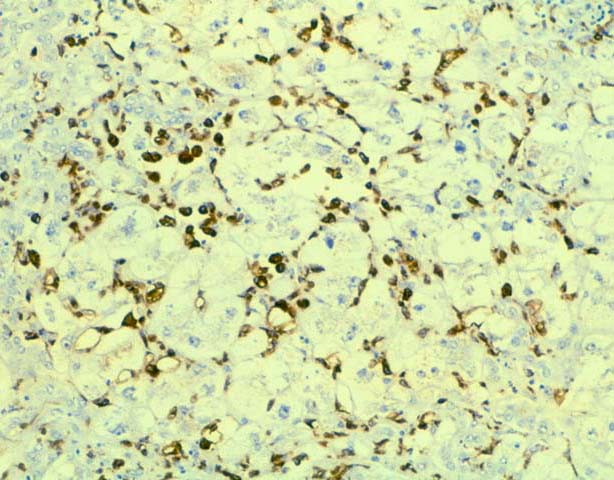

FCH is characterized by marked hepatocellular swelling, lobular disarray and cholestasis, with only mild or no portal or lobular inflammation. This is usually accompanied by cholangiolar proliferation at the interface zone, which is often combined with acute cholangiolitis and fibrosis surrounding the cholangioles. A well developed cirrhosis however, usually does not develop. Spotty acidophilic necrosis of hepatocytes and lobular inflammation, which are usual features of acute hepatitis, are inconspicuous in FCH. Overall, the histopathological features are similar, but not identical to, those described for "cholestatic" hepatitis in the general population. In HBV+ recipients, FCH is also characterized by massive expression of hepatitis B core antigen, which is seen in the same hepatocytes that show the degenerative changes such as cell swelling and steatosis and focal necrosis. A massive overproduction of the surface antigen can be seen in some cases, but these usually do not show the classical FCH histopathological or clinical profile. In these cases, there is marked cytologic distortion of the hepatocytes, lobular disarray and mild necro-inflammatory lobular activity, similar to HBsAg transgenic mice(23).

Differential Diagnosis

Non-viral causes of liver allograft dysfunction that can produce histopathological changes similar to those seen in FCH include ischemic injury, most often related to delayed hepatic artery thrombosis; adverse cholestatic drug reactions, and biliary tract obstruction. All of these insults can cause centrilobular hepatocellular swelling, Kupffer's cell hypertrophy, cholestasis and cholangiolar proliferation. The clinical history is extremely helpful in such cases: being aware that the patient is positive for HBV or HCV virus infection makes the pathologist cognizant of the fact that FCH should be in the differential diagnosis. The considerations are similar to those when establishing a histopathological diagnosis of amyloidosis: if you don't think of it, the diagnosis can be easily missed.

Histopathological changes that are helpful in making the correct diagnosis are usually quite subtle. Obstructive cholangiopathy is recognized by periductal edema surrounding the small and large bile ducts and portal neutrophilia and/or eosinophilia with true acute cholangitis. In contrast, there is no periductal edema, nor true acute cholangitis in FCH. Instead, there is acute cholangiolitis, or neutrophils surrounding ductular structures located in the interface zone. Interestingly, macrophages also frequently surround the hepatocytes and cholangioles, as well. Distinguishing between ischemic injury and FCH can be very difficult, especially if one does not think about the diagnosis of FCH. One subtle change that is helpful in some cases is the presence of hepatocyte macronucleoli in FCH, and their absence in ischemic injury. Any areas of coagulative necrosis or evidence of biliary obstruction or stricturing in the portal tracts is also helpful in distinguishing between the two, since ischemic injury frequently results in necrosis of the large, peri-hilar bile duct that leads to biliary sludge formation and "ischemic cholangitis(24, 25)". Finally, the clinical history is most helpful when trying to determine whether an adverse drug reaction is responsible for the constellation of findings described above. Since the time of onset of FCH is usually more than several months after transplantation, in cases of suspected adverse drug reactions, the clinical history should include mention of newly introduced pharmacological agent that is potentially hepatotoxic.

REFERENCES

|

|

|

|