Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of Cytomegalovirus(CMV) virus infection have greatly lessened the impact of this potential pathogen in the immunosuppressed liver allograft recipient(1, 2). However, it is still the most commonly encountered "opportunistic" viral infection of the liver allograft. As might be expected, the incidence of disease increases with the overall potency of non-specific immunosuppression. Symptomatic CMV infection is usually encountered during or after bolstered immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. treatment of rejection), between 3 and 8 weeks post-transplant. The infection may be the result of recrudescence in a carrier, transmission through blood products or the donor organ, or as an acquired disease. Seronegative recipients who receive seropositive donor organs are at the greatest risk of developing symptomatic disease(1-12). CMV infection is also more common in patients with co-existent recurrent hepatitis C virus hepatitis(13).

Clinical Presentation

Signs and symptoms of active CMV infection include fever, leukopenia and modestly elevated liver injury tests, although any organ system can be involved depending on the extent of viral dissemination(1, 2). More frequent complications include diarrhea, gastrointestinal ulcers and a mild hepatitis with low grade elevations of liver injury tests(1-12). Respiratory insufficiency and retinitis can occur when the disease is severe.

Occasionally, the clinical syndrome associated with cytomegalovirus disease after liver transplantation can closely mimic that seen with an Epstein-Barr virus infection. This presentation includes fever, lymphadenopathy, mild liver function abnormalities, and atypical lymphocytosis on the peripheral blood smear(1-12). Morbidity and mortality associated with CMV infection is usually associated with viral dissemination and involvement of the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. To our knowledge, CMV hepatitis has never led to significant liver damage or liver failure, despite the presence of numerous inclusion bodies in some cases.

Histopathologic Findings

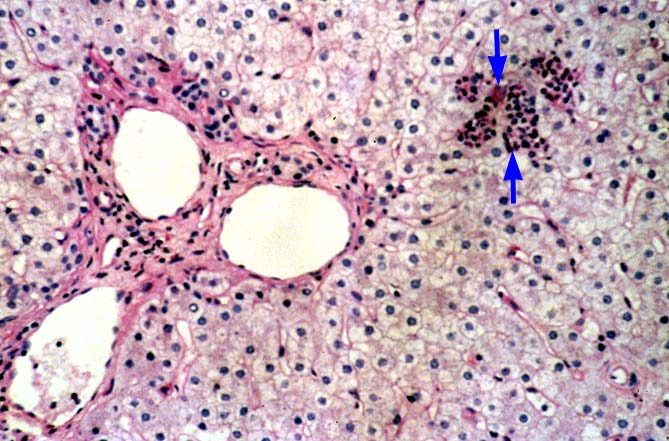

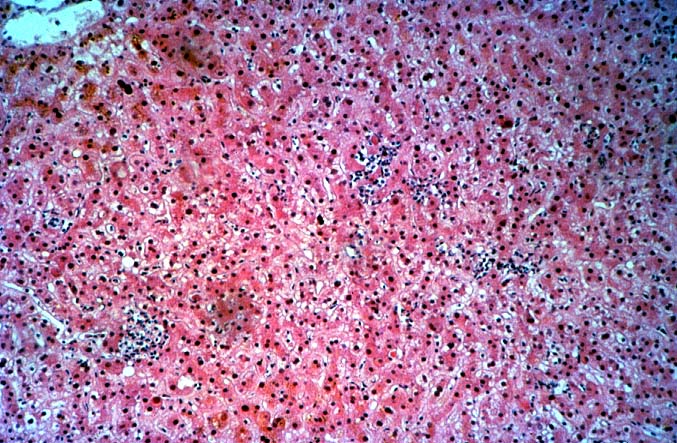

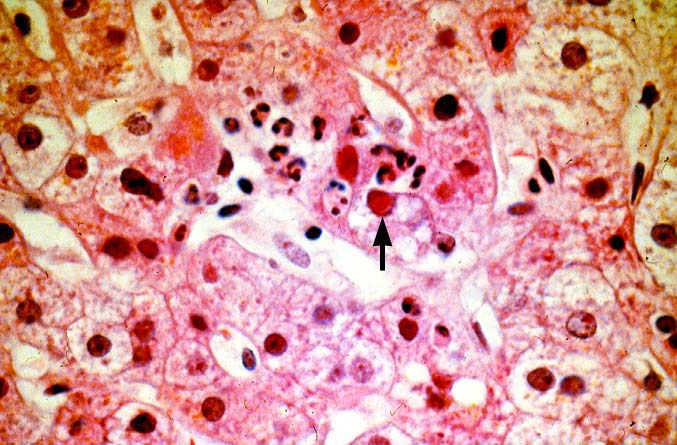

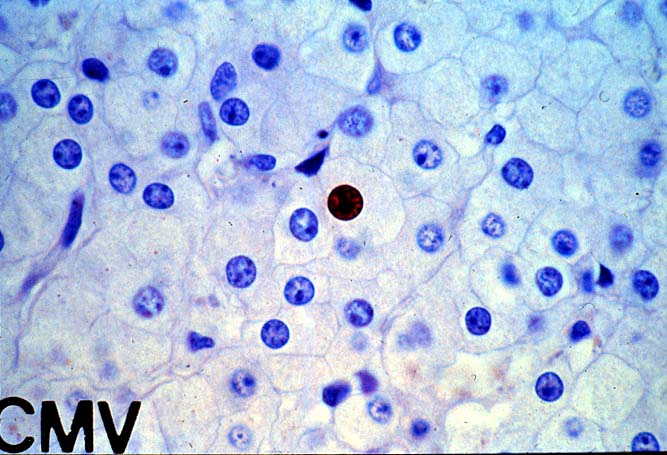

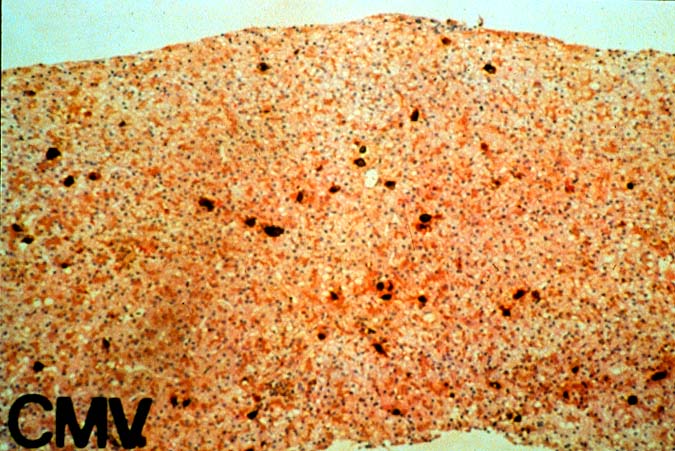

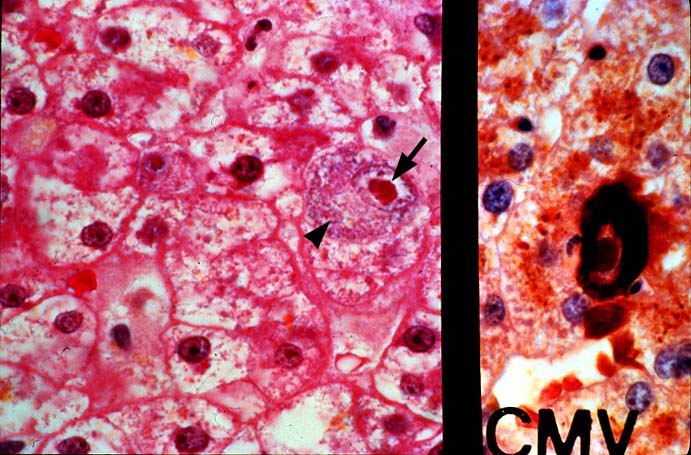

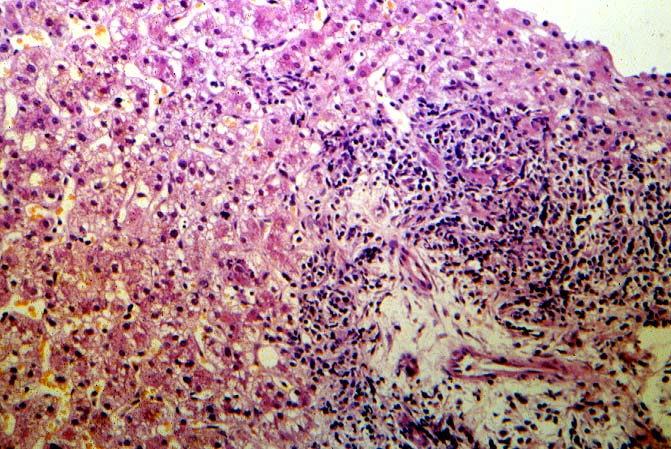

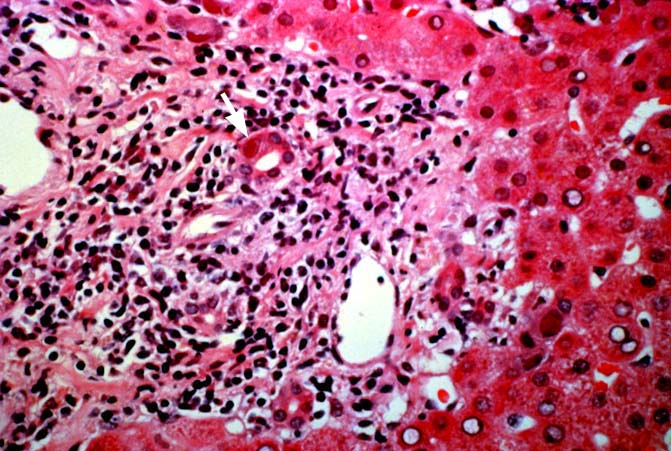

The histopathologic manifestations of active CMV infection depend in part, on the immune status of the host and whether the patient has been treated, or not, with any anti-viral agents. Classic cases are usually seen in heavily or over immunosuppressed patients; those who have no prior serologic evidence of CMV infection and in those not actively treated with anti-viral drugs. Early in liver allograft involvement, CMV antigens can be detected in sinusoidal cells (3). In fully developed cases, CMV hepatitis is usually characterized by mild lobular disarray and microabscesses or microgranulomas , which are small collections of neutrophils or macrophages, respectively, that are scattered randomly throughout the lobules. These are accompanied by spotty hepatocyte necrosis and Kupffer cell hypertrophy. Overall, this pattern of injury has been referred to by Colina(14) as, "disseminated focal hepatitis". Infected cells in or near the inflammatory foci show the cytomegalic change and often contain the characteristic nuclear and/or cytoplasmic inclusions. Any type of liver cell can be infected, and typically, there is a large intra-nuclear eosinophilic inclusion, which is surrounded by a clear halo. The chromatin is pushed to the periphery toward the nuclear membrane. The cytoplasm may or may not contain small basophilic or amphophilic inclusions, a feature that is helpful in distinguish CMV infected cells from the Herpes Simplex virus or Adenovirus infection.

Improved immunologic monitoring, effective pharmacological therapy and immunoprophylaxis, have made overwhelming CMV infections, like those described above, less common(1, 2). With the current pharmacological arsenal, the overall histopathological pattern of the disease is the same, but classic inclusion bodies that enable the pathologist to make the diagnosis on H&E sections alone, are not often seen. Currently, infected cells often show slight cytomegalic change and inclusion bodies, if present, are often fragmented or smudged, requiring immunohistochemical confirmation to ascertain the diagnosis. In some cases, neither the inclusion bodies nor cytomegalic change are detected, and immunohistochemical detection of viral antigens is required to make the diagnosis.

"Activated" or rapidly dividing tissues such as young granulation tissue, proliferating cholangioles seen in ischemically damaged livers, edges of infarcts, abscesses or other intraparenchymal defects are fertile soil for CMV growth(15). When such tissue is encountered, a more careful search for CMV is warranted.

CMV hepatitis also often shows a mild plasmacytic or lymphoplasmacytic portal infiltrate, which can be associated with focal bile duct inflammation and damage. Whether this ductal injury is related to viral infection alone, rejection as a consequence of upregulation of foreign MHC antigens (1, 16-21), or both, is uncertain. Late acute rejection, occurring more than several months after transplantation, has been associated with CMV infection(22). Regardless of the pathophysiology of ductal damage, treatment of the patient whose shows tissue evidence of CMV infection with anti-viral agents is needed to help control the damage. Whether concomitant anti-rejection therapy is helpful or harmful, is a controversial issue.

More importantly, CMV infection/hepatitis has also been associated with the development of chronic rejection in several(16-18, 20, 21, 23-28), but not all studies (29, 30). The precise mechanism by which CMV leads to ductal damage and loss is under intense scrutiny. Persistence of the CMV antigens has been detected in the bile ducts in patients with chronic rejection(20, 21).

Differential Diagnosis

CMV hepatitis is most difficult to diagnose when the typical microabscesses and viral inclusions or cytomegalic change are not present. Such cases can be extremely hard to distinguish from the acute hepatitis caused by hepatotrophic hepatitis B or C viruses. Distinguishing such cases from EBV hepatitis can also be problematic. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that the onset of all of these viral syndromes, is very similar, and typically occurs between 4 and 8 weeks after transplantation. Moreover, making this distinction is quite important, since medical therapy for the hepatotrophic virus is much different than that use to control opportunistic viral infections.

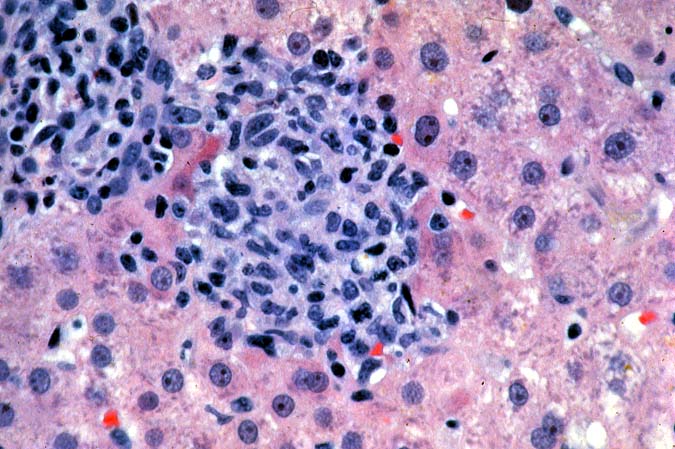

Paying close attention to fine histopathological details on routine sections can often be helpful in making the correct diagnosis in such cases. In general, CMV causes less lobular disarray and hepatocyte swelling than the hepatotrophic viruses. In addition, the lobular inflammation seen with hepatitis B and C consists primarily of isolated lymphocytes permeating the sinusoids, whereas in CMV the lobular inflammation often contains neutrophils, which cluster into small aggregates or microabscesses. Kupffer's cell granulomas or microgranulomas can be seen in both disorders, but are more common with CMV. Portal inflammation is seen in CMV and with hepatitis B and C. In the latter however, it is not uncommonly coalesced into nodular aggregates, which is not typical for CMV hepatitis.

Some cases of CMV hepatitis without inclusion bodies can also be difficult to distinguish from EBV hepatitis. Both may be characterized by a mild lymphoplasmacytic portal and lobular infiltrate, containing blastic and atypical lymphocytes(31). Microgranulomas are usually seen in the lobules. The more severe the cytological atypia in the infiltrative cell population and the greater the number of such cells makes a diagnosis of EBV more likely.

In the end, when inclusion bodies are not found, the correct diagnosis is made by combining the histopathological findings with the results of adjuvant tests. These include serum antigenemia assays, viral cultures, RT-PCR, immunoperoxidase staining and in situ hybridization for viral antigens or nucleic acids (EBV). In our experience, clinical monitoring for CMV is guided primarily by serum antigenemia assays. The definitive diagnosis of CMV is based on identification of classical inclusion bodies or routine immunoperoxidase staining for a cocktail of early and late CMV antigens. This approach has been the best compromise between diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, cost and practicality.

Even when inclusion bodies are detected, it may be difficult to distinguish CMV from herpes simplex, Varicella-Zoster and adenovirus infection. One important distinguishing feature of CMV is the presence of the small basophilic or amphophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which are not seen with these other viruses. In addition, HSV and VZ also cause circumscribed zones of coagulative necrosis that are not encountered with CMV. Adenovirus also causes punctate areas of hepatitis in the liver allograft, similar to CMV, but the collections of inflammatory cells in adenovirus are usually much larger and often associated with areas of confluent necrosis. In contrast, the necrosis seen with CMV is spotty, usually limited to isolated hepatocytes.

REFERENCES

|

|

|

|