ADENOVIRAL HEPATITIS

Introduction and Pathophysiology

Adenoviral infection and disease after liver transplantation is

largely limited to the pediatric population (1-3), although it

occasionally can be seen in adults. The difference in frequency

between the two different age populations is presumably related

to prior protective immunity, much like the situation seen with

CMV, EBV and the other "opportunistic viral infections..

Viral subtypes 1, 2 and 5 have been isolated from the lung, gastrointestinal

tract and liver in patients with fever, respiratory distress,

diarrhea, and liver dysfunction(1-3). The onset of symptoms attributable

to adenoviral infection usually occurs between 1 and 10 weeks

after transplantation. Tissue biopsies and histopathological analyses

are used to ascertain the diagnosis. Liver involvement with frank

hepatitis is most often caused by subtype 5. However, viral subtypes

2, 11 and 16 have been associated with hepatitis in the general

population and therefore, could be expected to behave similarly

in liver allograft recipients(1-3).

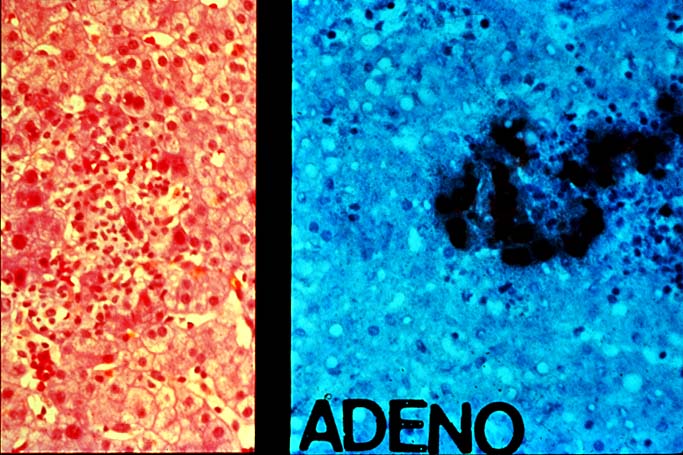

Histopathologic Findings

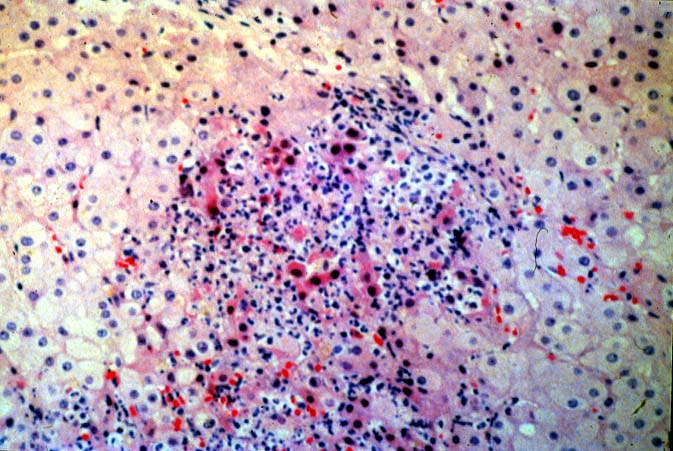

Some experience is usually required to establish the diagnosis

with certainty and therefore, immunohistochemical confirmation

of the presence of viral antigens can be very helpful. The most

characteristic changes on routine light microscopy, are the presence

of "pox-like" granulomas, consisting almost entirely

of macrophages, which are spread randomly throughout the parenchyma,

encompassing small groups of necrotic hepatocytes (1-3). In other

cases, the granulomatoid collections of macrophages are replaced

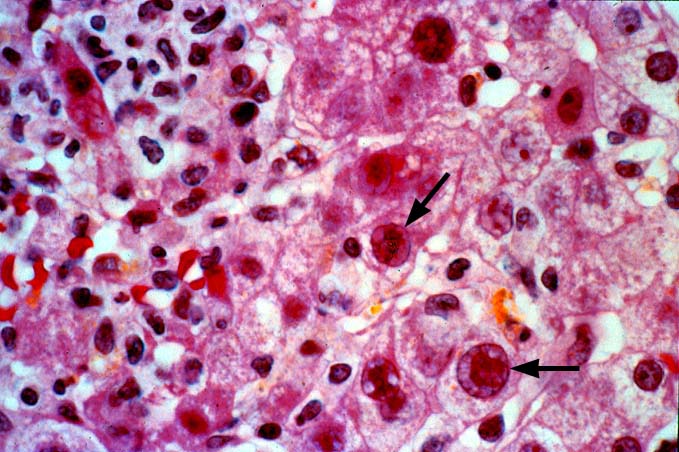

by necrosis that can be rather extensive. Adenoviral inclusions,

when identifiable, are often located near the edge of the necrotic

zones and/or granulomas. They are characterized by a crowding

of chromatin towards the nuclear membrane, imparting a muffin-shape

appearance to the nucleus. Immunohistochemical staining are confirmatory.

Portal inflammation is variably present, but subendothelial inflammation

of portal and/or central veins and bile duct damage are not usually

seen.

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes deep fungal or mycobacterial infections, CMV and HSV-VZ, ischemic necrosis, and non-specific granulomatoid collections of macrophages, which are not uncommon in liver allograft biopsies. Obvious adenoviral inclusions clinch the diagnosis. However, inclusions are not always identified or easily distinguished from other types of viral inclusions. The granulomas associated with adenovirus consist almost entirely of macrophages, are much larger than the "micro-granulomas" of CMV, and multinucleated giant cells are rare. In contrast, CMV causes cytomegaly of the involved cell, and CMV can produce both eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear halo, and basophilic or amphophilic small cytoplasmic inclusions. In contrast, Adenovirus usually does not cause significant cytomegaly. In addition, the infected nuclei are "smudgy-appearing" and there are no cytoplasmic inclusions. The hepatocyte necrosis associated with Adenovirus is generally less than that seen with Herpes Simplex or Varicella-Zoster hepatitis. However, in other cases, the two(Adenovirus and Herpes Simplex or Varicella/Zoster) can appear quite similar.

The zones of ischemic necrosis seen with vascular compromise of one sort or another, can appear similar to the necrosis seen with Adenovirus and HSV-VZ. However, in the former, the necrosis almost always shows a lobular or zonal distribution whereas in the latter, the distribution of necrosis is apparently random. In addition, virally infected cells are usually absent in ischemic damage.

Non-specific granulomatoid collections of macrophages are not infrequent in liver allograft biopsies. However, there usually is little other evidence of tissue damage and the clinical profile is not typical of a viral syndrome. In addition, typical inclusion bodies are not seen.

A not insignificant number of cases will remain where significant

pathological changes are seen, but inclusion bodies are not present,

or the pathologist is unsure. In such cases, information gained

from ancillary studies can provide useful information. For example,

microbiologic cultures of the biopsy and negative special stains

for granuloma-causing organisms make fungal and mycobacterial

infections less likely. The clinical syndrome and findings provide

additional useful information. Finally, the presence of Adenoviral

antigens confirmed by immunohistochemical staining is confirmatory.

REFERENCES

|

|

|

|