Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease affects approximately 1% of renal transplant recipients, and allograft involvement is reported in 36-100% of cases. In healthy individuals EBV causes a self limited infectious mononucleosis syndrome. However in the setting of excessive immunosuppression, impaired anti-viral defenses permit an uncontrolled proliferation of EBV transformed B-cells, thereby resulting in the syndrome of PTLD.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation varies from a mild febrile syndrome with pharyngitis and lymphadenopathy to aggressive B- cell lymphomas involving nodal and extranodal sites. The disease may sometimes be limited to the allograft.

Pathology

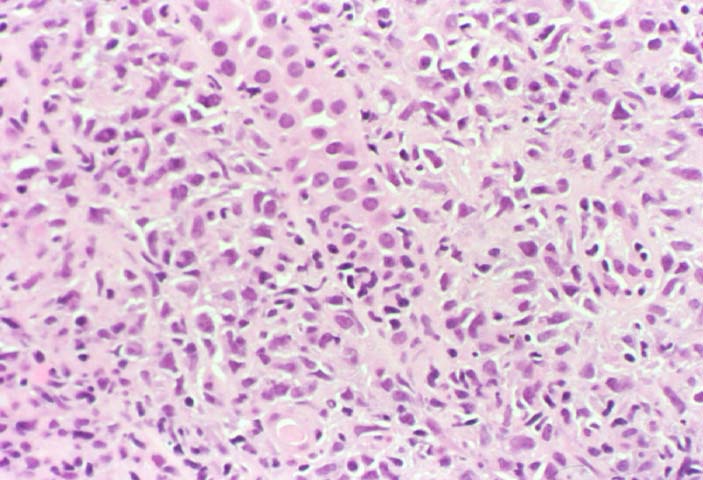

The nomenclature used in the histologic classification of PTLD's lesions varies in different medical centres. We tend to categorize these lesions as EBV positive lymphadenitis (resembling infectious mononucleosis), polymorphic PTLD's or monomorphic PTLD's (Wu et al, 1996). Another well accepted three tier classification system uses the terms plasmacytic hyperplasia,polymorphic B-cell hyperplasia/polymorphic B-cell lymphoma and immunoblastic lymphoma/multiple myeloma (Knowles et al, 1995). Unfortunately, morphologic appearances do not reliably predict ultimate clinical prognosis.

Differential diagnosis

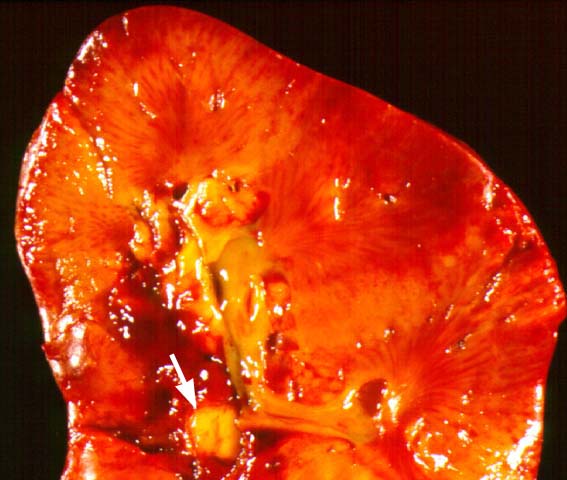

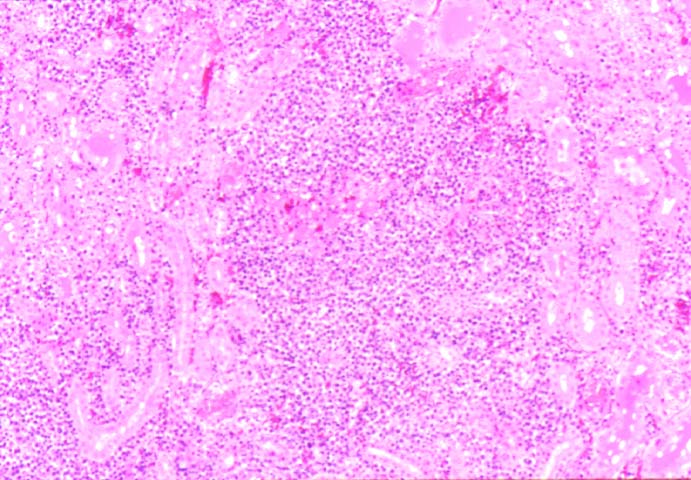

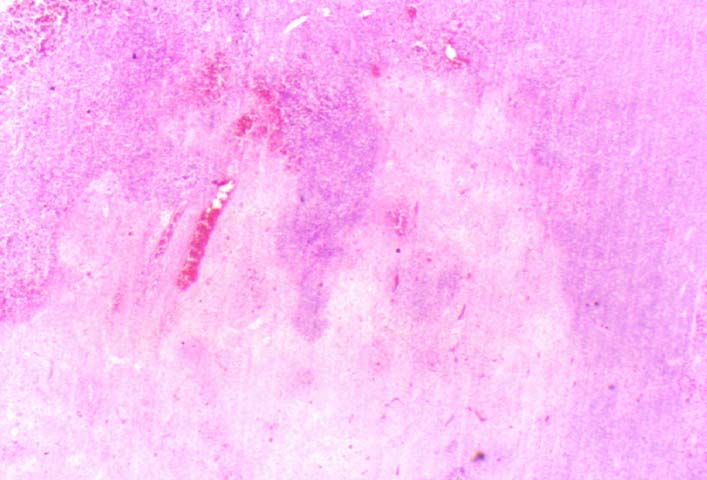

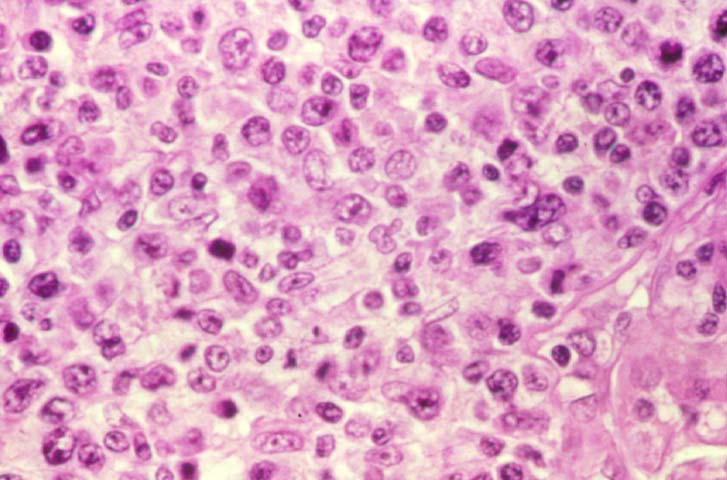

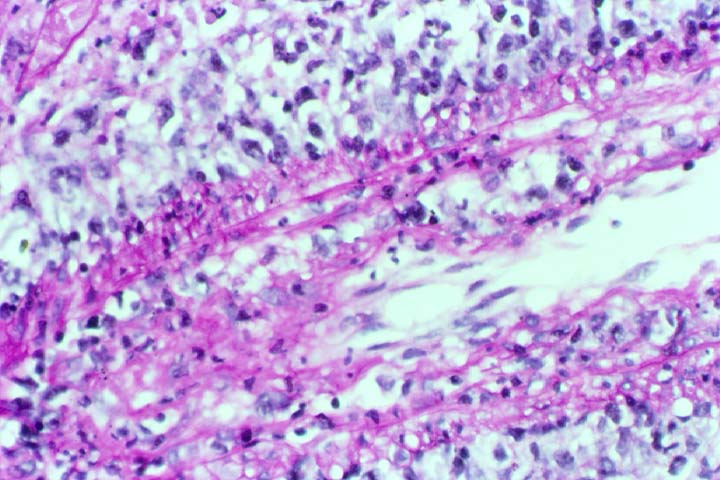

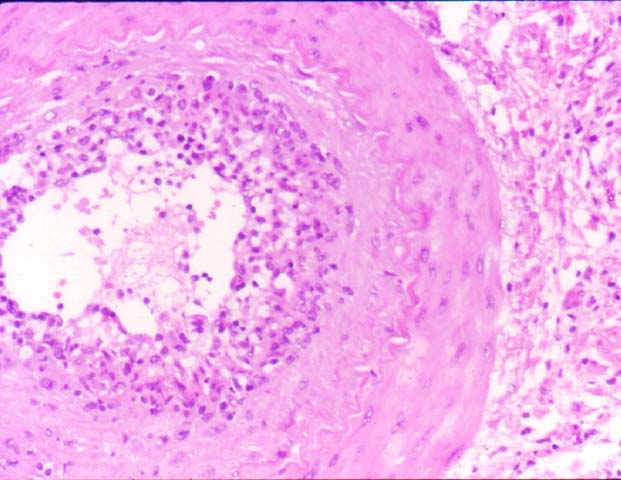

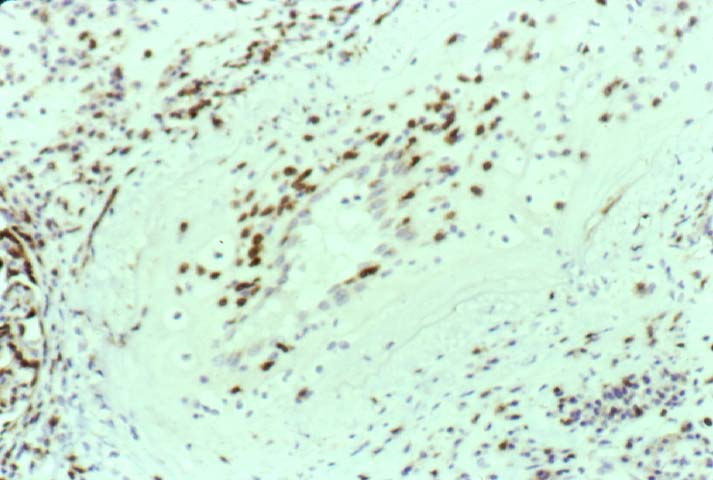

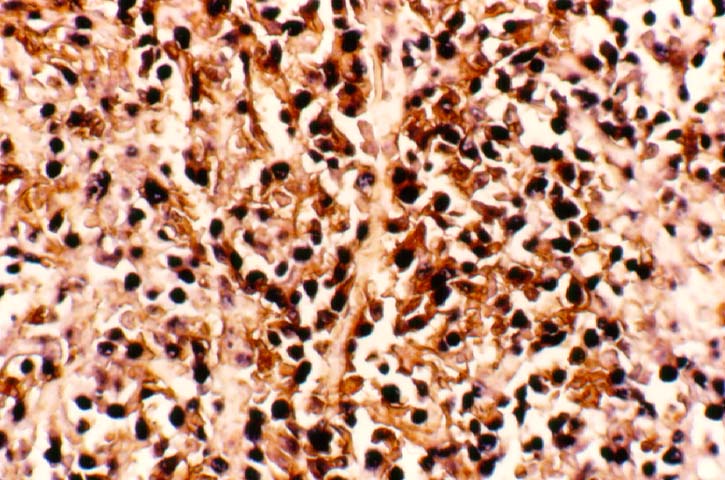

Biopsy distinction between renal PTLD and severe acute rejection is important, since the appropriate treatment is reduction of immunosuppression for PTLD, but aggressive anti-T cell therapy for severe acute rejection. PTLD typically shows expansile nodular mononuclear infiltrates with irregular foci of geographic necrosis. These nodular infiltrates must be distinguished from follicular hyperplasia occurring in rejection due to allogeneic stimulation. The infiltrates in PTLD generally show the entire spectrum of lymphocyte differentiation, including immunoblasts, plasma cells, large cleaved/non-cleaved cells, and small round lymphocytes. Cells with significant nuclear atypia can usually be detected. Some biopsies present a monotonous appearance indistinguishable from conventional lymphomas. Although not as frequently found as in severe rejection, tubulitis can be demonstrated in relation to PTLD cells. Likewise, interlobular arteries entrapped within PTLD lesions may show lesions resembling vasculitis, which should not be confused with rejection. Infiltration of the hilar soft tissues or nerves can be seen in PTLD as well as in severe acute rejection.

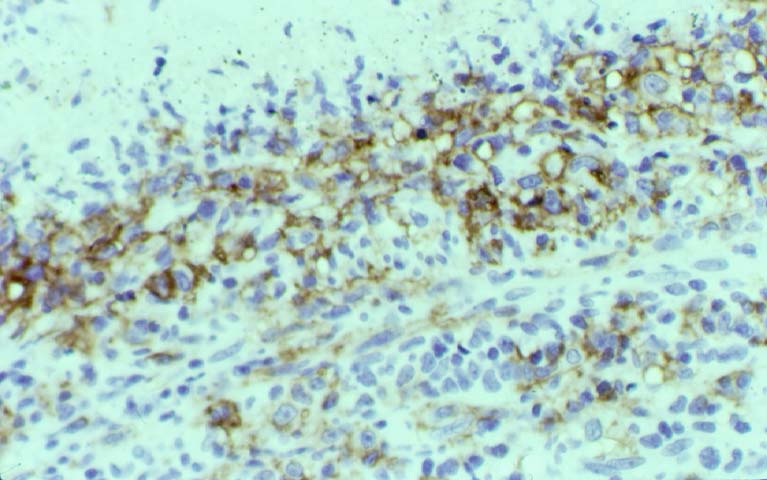

While the quality of the cellular infiltrate, its expansile nature, and the presence of serpiginous necrosis are helpful criteria in the separation of PTLD and severe acute rejection on routine light microscopy, difficulties can be encountered with limited biopsy material. In the latter circumstance, the final diagnosis must await the results of immunophenotyping, and EBV in-situ hybridization. With rare exceptions, PTLD lesions are B-cell preponderant and EBV positive, while rejection is associated with a primarily T-cell infiltrate, which is EBV negative. In lesions with significant numbers of plasma cells, staining for kappa and lambda light chains is a convenient way of identifying lesions which are clearly clonal. If sufficient fresh tissue is available, immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and oncogene studies can be performed to help in diagnosis, and to generate information relevant to ultimate prognosis. It is worthwhile remembering that PTLD and severe acute rejection are not always mutually exclusive diagnoses. Since PTLD frequently arises in the setting of severe acute rejection treated by OKT3, evidence of both processes can be found in some specimens.

Treatment

Reduction of immunosuppression is customary as this allows the host immune response to recuperate, and potentially mount a successful anti-EBV response. In cases with a mild viral syndrome, 50% reduction in the dose of cyclosporine or tacrolimus may be initially attempted. In cases with aggressive PTLD, complete discontinuation of immunosuppression is desirable. In our hands, this results in rejection in 50% of the patients, roughly one half of whom subsequently lose their graft. Therapy with acyclovir, alpha-interferon, and human lymphokine activated killer cells (LAK cells) has been used sporadically for the treatment of PTLD, but controlled trials evaluating their actual efficacy have not yet been performed. When the disease is localized to the allograft, allograft nephrectomy can effectively cure the patient. However, cases with multisystem disease may progress to a fatal outcome.

References

|

|

|

|